Buying a Muni Below Par? Reasons to Think Twice

Thinking about buying a municipal bond at a price below its par value? You may want to think twice, because if it's acquired at too large of a discount it could be subject to an additional tax, known as the "de minimis" tax, which would take a bite out of the after-tax return.

In short, the larger the discount, the greater the risk that an investor will face a higher tax rate. Here are some issues to consider.

What is a discount?

Municipal bonds, or munis, are usually issued with a $1,000 par value, which is the amount you can expect to receive when the bond matures. However, after the initial issuance date, a muni's value can rise and fall in the secondary market. Events such as rising interest rates or deteriorating credit quality can cause the value of the bond to fall below $1,000. When that happens, the bond is trading at a discount.

Do I have to pay taxes on the discount?

In most cases, yes. If you acquire a muni at a discount, you may have to pay taxes on the difference between the par value and the acquisition price. Generally, the taxes are due in the tax year the bond matures, is sold or is transferred to another entity or person, but you may also choose to pay the tax annually.

The purchase date matters: If you acquired a discount muni before April 1993, you'll have to pay capital gains tax only. For discount bonds acquired after that, you could be subject to the capital gains tax, ordinary income taxes (which are generally higher) or a combination of both.

What taxes do I have to pay on the discount?

That depends on the price at which you acquired the bond. The de minimis rule says that for bonds acquired at a discount of less than 0.25% for each full year from the time of purchase to maturity, gains resulting from the discount are taxed as capital gains rather than ordinary income. Larger discounts are taxed at the higher income tax rate.

Imagine you wanted to buy a discount muni that matured in five years at $10,000. The de minimis threshold would be $125 (10,000 x 0.25% x five years), putting the dividing line between the tax rates at $9,875 (98.75) (the par value of $10,000, minus the de minimis threshold of $125).

For example, if you paid $9,900 (price of 99.00) for that bond, your $100 price gain would be taxed as a capital gain (at the top federal rate of 23.8%,1 that would be $23.80). If you received a bigger discount and paid $9,500, your $500 price gain would be taxed as ordinary income (at the top federal rate of 40.8%,2 that would be $204.00).

De minimis thresholds for a $10,000 muni

What about for bonds that are already issued at a discount?

Not all discount bonds are automatically subject to taxes, though. Occasionally, a municipality will issue bonds at a discounted price, known as an original issue discount, or OID. For such bonds, the OID is treated as part of the bonds' interest income and is usually not subject to capital gains or ordinary income taxes. Investors can usually determine if a bond is an OID by looking at the offering statement or the bond description page on Schwab.com.

However, once an OID bond is trading in the secondary market, if the price drops below the adjusted OID price, it may be subject to the discount rules and subsequent taxes.

What if I sell my munis before maturity? Do I still need to pay the tax?

Generally, we suggest that individual investors hold their bonds until maturity. However, there may be reasons why many investors need, or choose, to sell bonds before maturity. If you sell earlier and you receive a price greater than your cost basis, the gain will be subject to capital gains tax. Cost basis is your acquisition price after adjusting for any premiums paid or discounts received. You may also have to pay ordinary income taxes on the accretion of the market discount as well.

Determining the cost basis of an individual bond can get complicated, as there are special reporting rules that govern the adjustments to a bond's acquisition price. For bonds held at Schwab, you can find your adjusted cost basis by logging into schwab.com/positions and clicking the "unrealized gain/loss" tab.

What about state income taxes?

Up to this point, we have only discussed the effect that a discount has on federal taxes, but it may have an impact on state income taxes as well. It varies from state to state, but if the purchase price is less than the de minimis threshold, the discount may be taxed as ordinary income at the state level, too. This may be an unwelcome surprise, especially for an investor in a state with high state income taxes.

For example, consider an investor in the top tax income brackets in California, which are 40.8% for federal2 and 13.3% for state. In this hypothetical example, the investor bought a $10,000-face-value, five-year California bond with a 2% coupon at a price of 95—or $9,500. Barring default, they will receive $200 income per year for a total of $1,000 plus the $500 gain back to the maturity value. Prior to paying taxes, they would expect to receive $1,500 total over the entire five years. However, because the purchase price of 95.0 is less than the de minimis threshold, they would have to pay ordinary income taxes on the $500 gain. For this example, that would be $204.00 in federal income taxes and an additional $66.50 in state income taxes. So instead of receiving $1,500, they would net roughly $1,230 after paying taxes—or 18% less than the $1,500 amount.

Are there things that I should look out for when buying a muni?

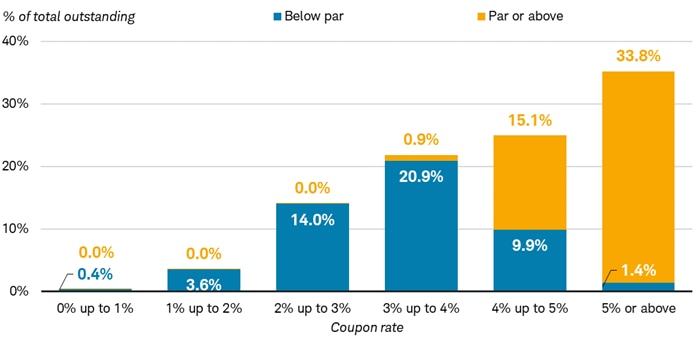

When calculating the de minimis threshold, the price is the most important factor. However, coupon structure matters when considering buying individual bonds, because bonds with lower coupons are more likely to trade below par. For example, roughly half of all municipal bonds are trading below par, but the vast majority of those have a coupon that is below 4%. Munis with a coupon that is 5% or above account for about a third of all outstanding munis and most are trading above par.

Munis with lower coupons are more likely to trade below par

Source: Bloomberg, as of 5/8/2025.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

This matters not just because it impacts the current price, but it could also impact the future price. For example, if yields move higher, the price of a lower-coupon bond would drop more than a higher-coupon bond. This could cause the lower-coupon bond to cross the de minimis threshold. The current holder of that lower-coupon bond won't be subject to the de minimis tax. However, if they chose to, or had to, sell it, it would likely be at a lower value and with less liquidity than a muni that wasn't subject to the de minimis tax.

What to consider now

Municipal bonds offer tax advantages and could make sense in the portfolios of many income-focused investors. However, the details of what municipal bonds you purchase matter because you could end up paying unexpected taxes. If you have questions about your portfolio, consult IRS Publication 550, "Investment Income and Expenses," or check in with your tax advisor.

1 This 23.8% rate includes the 20% top capital gains tax rate plus the 3.8% Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT), which applies to taxpayers whose income is above statutory thresholds.

2 This 40.8% rate includes the top 37% federal income tax bracket plus the 3.8% NIIT.